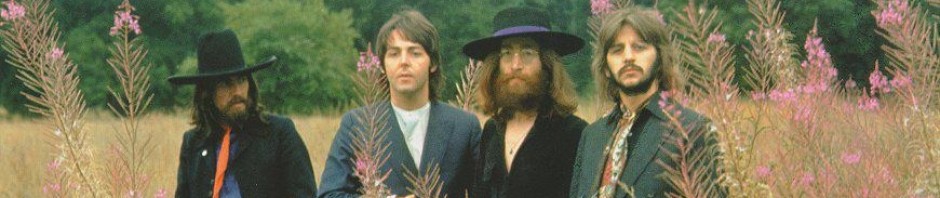

The Fab Four and Hitsville USA made a great combo, as Kit O’Toole recounts in this expanded version of an article published in Beatlefan #250.

When The Beatles first conquered the U.S. in February, 1964, they forever changed American music. British groups impacted the charts like never before, folk artists like Bob Dylan “went electric,” and psychedelia later would infiltrate pop. The formidable songwriting team of Lennon-McCartney, as well as George Harrison’s rapidly growing composing skills, also signaled a new era for rock: self-contained bands, or artists who composed their own music. This posed a threat to the Brill Building writers and other professional songwriters who, until The Beatles’ arrival, had dominated the American market. Yet one label managed to compete with The Beatles during the 1960s, becoming not only the most successful independent record company in history, but also the most successful Black-owned business in America.

Motown, founded by songwriter and entrepreneur Berry Gordy, broke down barriers between R&B and pop music by fusing various music genres, such as symphonic elements, jazz, rock, psychedelia, funk and pop; writing lyrics with universal meaning that were clever, intelligent and memorable; and emphasizing strong beats, using percussion and bass (foreshadowing disco and hip hop).

The Beatles learned from the Motown Sound, covering their early songs and emulating Smokey Robinson’s smooth singing style and eloquent songwriting techniques. In turn, Motown artists thanked The Beatles for their support by covering their songs. Motown, founded in 1959, and The Beatles would prove to have a symbiotic relationship.

The Birth of Motown

By the fall of 1957, Gordy had tried several careers: boxer, owner of a jazz record store, and an employee at the Ford motor plant. With a wife and kids to support, he needed to settle on a lucrative profession, and fast. His true passion remained music, specifically songwriting. Fortunately, he lived in Detroit, which was experiencing a musical renaissance in the 1950s; thanks to acclaimed music programs in high schools and a plethora of music clubs and theaters, the city teemed with talent and enthusiastic audiences.

Gordy frequented many of those clubs, hoping to find artists willing to record his compositions. One such venue, the Flame Show Bar, offered him a unique opportunity to mingle with artists and their managers: his sisters, Anna and Gwen, headed the photo and cigarette concession stands. Gordy would become friendly with Flame house band members Maurice King and Thomas “Beans” Bowles, Earl Van Dyke and James Jamerson — all of whom later would lbecome Motown studio or touring musicians.

But, another connection would prove key in starting Gordy off on his music career: Al Green, Jackie Wilson’s manager. Chatting with Green at the Flame, Gordy pitched his songs; the manager told Gordy to stop by his office the next day.

That meeting resulted in the pairing of Gordy with another songwriter, Roquel “Billy” Davis (who wrote under the pseudonym “Tyron Carlo”), and they would go on to pen the Wilson classics “Reet Petite” and “Lonely Teardrops.”

It was during this time that Gordy developed his songwriting formula, as outlined in Gerard Early’s “One Nation Under a Groove: Motown and American Culture”:

- Always use present tense

- Never overdo the hook

- Make sure the song has a hummable melody (something faintly resembling an already familiar melody)

- Find originality in the song’s concept, how the lyrics are phrased, and in its rhythm

- Singer should serve the song, the song should not serve the singer

While writing for Wilson, Gordy also met another aspiring songwriter and performer who auditioned for Green: Smokey Robinson, who brought his group the Miracles. Green turned them down, but Gordy was taken with their sound and felt Robinson held great potential as a songwriter. The two would form a lifelong friendship and become business partners, as Gordy transitioned from songwriter to business owner.

While Gordy enjoyed these early successes, he learned a hard truth: as a songwriter, he earned a fraction of the money the main performer, the producer and the label owner made. At first, Gordy believed he could profit more as a producer, so he would rent studio space, record artists, and broker deals with record labels for distribution. Once he learned that he still earned little money, Gordy (with Robinson’s encouragement) decided to form his own company. In 1959, with an $800 loan from his family trust, he formed the Tamla label, based on his experience working at the Ford plant; namely, production could be organized efficiently and automated for the highest quality. Everyone would have their own roles and, with few exceptions, never would overlap (e.g. composers wrote songs, producers produced, and artists recorded their vocals and played their instruments). Gordy also founded a publishing company, Jobete, to ensure ownership of the songs. As the label grew, he formed the subsidiary label Motown, shifting groups there and retaining solo artists on Tamla. By 1960, Gordy incorporated the company as the Motown Record Corp.

The record credited with kicking off Motown is Marv Johnson’s “Come to Me,” first issued on Tamla in 1959 and marking Berry’s debut as songwriter and producer. It became a Top 30 pop hit, and peaked at No. 6 on the R&B charts, a very promising beginning for the upstart label. The company’s next single, however, would make a much bigger dent on the charts (and set the tone for the Motown sound): “Money (That’s What I Want),” the Barrett Strong track that peaked at No. 2 on the Hot R&B Sides chart and No. 23 on the Hot 100 chart. While Tamla released the record locally in 1960, “Money” was distributed nationally via his sister Anna Gordy’s label, Anna Records, through a deal with Chess Records. Gordy and Strong wrote the majority of the song, although, according to Gordy’s 1994 autobiography “To Be Loved,” his then-secretary, Janie Bradford, contributed the lines “Your love give me such a thrill / But your love don’t pay my bills.”

Around this time, Berry said, the distinctions between “white” and “black” music were becoming fuzzier. R&B was black, pop was white. But, with the rock explosion and Elvis Presley’s popularity, that difference began to change, and “Money” represents that shift.

As Tamla/Motown grew, so did its talent roster. The Funk Brothers, its formidable house band, drew from the local talent playing in Detroit jazz and blues clubs. Hank Cosby (saxophone), Benny Benjamin (drums), Jamerson (bass), Van Dyke (piano), Eddie “Bongo” Brown (percussion), and Robert White, Joe Messina and Eddie Willis (guitars), are just some of the many names that comprised the group that played on every recording. Playing in what they called the “snakepit” (the basement studio of Hitsville, USA in Detroit), they were expected to crank out three to four songs during every three-hour session. An average workday consisted of two of these three-hour sessions, occasionally three or four. Due to their vast expertise, they could handle songs thrown at them at such a rapid rate, even though they often had no prior knowledge of the tracks’ titles or their intended performers.

Motown’s assault on the charts began in 1960, when “Shop Around” by Robinson and the Miracles became the label’s first million-seller and peaked at No. 2 on the pop charts. Co-written by Robinson and Gordy, the track (originally intended for Strong) showcased Robinson’s silky voice and clever lyrics, and the Funk Brothers’ trademark sound. The following year proved even bigger, with the Marvelettes’ “Please Mr. Postman” zooming all the way to No. 1 on the pop charts. From then on, the label boasted an enviable amount of talent: Mary Wells, the Supremes, the Temptations, the Four Tops, Marvin Gaye, Martha Reeves and the Vandellas, and Stevie Wonder. The in-house songwriters proved to have an ear for making hits, with the legendary team of Brian Holland, Lamont Dozier and Eddie Holland, as well as Norman Whitfield, Ashford and Simpson, and, of course, Robinson, penning classics that competed with — and even influenced — the British invasion groups.

What Is “The Motown Sound”?

The “Motown Sound” also became a key element of their success, and much of it resulted from budget constraints, adapting to a small space, and transistor radios. For starters, Studio A’s live room was just a simple rectangle, with ceilings only slightly taller than average — not exactly a cavernous space like Abbey Road’s Studio 2. The Steinway grand piano dominated the space, leaving relatively little room once mics, chairs and music stands were set up, and the numerous cables dangling from the ceiling earned this space the nickname “the snake pit.” But, despite its relatively modest facility, Motown kept up with the cutting edge of recording technology. Starting off with a primitive two-track setup, Hitsville graduated to a three-track format in 1961, before moving to eight-track in the mid-’60s and 16-track by the end of the decade.

The move to more tracks did a lot to shape the Motown Sound, and the difference can be heard clearly by comparing an early song like “Heat Wave” by Martha & The Vandellas with the fuller sound of “Cloud Nine” by the Temptations. Track limitations on the former required the tambourine, snare and hi-hat all to share a single mic, while the latter features dedicated tracks for auxiliary percussion, multiple guitars and backup vocals. Due to space limitations, there was no room for a vocal booth, so they made one out of the hallway that led from the control room to the stairs that took you into the studio. There were no windows, so they couldn’t see the singer, and had to communicate via microphones. They had to place the first echo chamber in the downstairs bathroom, so a guard was positioned outside the door, so no one flushed during recording. Later they adopted an attic area for an echo chamber, which made the voice sound fatter and gave the recording a bigger sound. Later, a German electronic echo chamber called EMT was installed in the basement.

In addition, because there was no room for large amps in studio, the guitars and bass were plugged right into the console and were heard through the room’s one speaker. Before a session, the guitar players would adjust their volume to a level they were never to exceed. These necessary adaptations led to the prominent sound of Jamerson’s bass, as well as the rhythmic guitars, both signatures of Motown records.

Another factor involved consumer technology. By 1965, more than 12 million transistor radios were being purchased a year. In addition, in 1963 about 50 million radios had been installed in car dashboards. Shrewdly, Gordy geared his music toward these mediums. Chief engineer Mike McClain built a small, tinny-sounding radio designed to approximate the sound of a car radio. The high-end bias of Motown recordings can be traced partially to this technique, thus adding another dimension to the label’s distinctive sound.

Overall, Dennis Coffey, a guitarist who joined the Funk Brothers later in Motown’s history, summarized the essential elements of the instrumental sound in his 2004 autobiography “Guitars, Bars, and Motown Superstars”:

- Percussion: occasionally using two drummers with gospel tambourine and bongos

- Guitar backbeat: sharp-sounding guitar part played high up on neck along with snare drum (beats two and four)

- Funky, melodic bass sound

- Songs themselves: innovative, jazz-style chords, melodic chord changes

- Lush orchestra with horns and strings

- Vocalists have a slick, urban sound

Motown Invades the UK and Encounters the Beatles

While Motown records were not distributed under their own label n the U.K. until 1965, Gordy struck a deal with Decca’s London American imprint to release records as early as 1959’s “Come to Me.” Thus, The Beatles heard and purchased 45s such as “Money” and “Shop Around,” although these singles initially had little impact on the British charts. They did, however, receive airplay on pirate radio stations, where The Beatles and members of the Rolling Stones were listening keenly to American records.

Before Gordy could sign a better distribution deal, The Beatles were about to introduce the British public to Motown. On March 7, 1962, the group recorded their radio debut on a BBC show, entitled “Teenager’s Turn — Here We Go,” at the Playhouse Theatre in Manchester, the first time The Beatles appeared on BBC radio. In front of 250 people, the band performed three songs: “Dream Baby,” “Memphis” and “Please Mr. Postman.” When the group launched into the final song, it marked the first time the song — or any Tamla Motown song — was played on the BBC. The Beatles may not have realized it at the time, but the group broke the Motown Sound to the wider British listening public.

Because of that, Gordy could negotiate for a better distribution deal. After a short-lived deal with Philips’ Fontana imprint, Gordy signed a longer term agreement with Oriole Records in September, 1962, under which 19 singles were released over a yearlong period, including “Do You Love Me” by the Contours, “Fingertips” by Stevie Wonder and “Stubborn Kind of Fellow” by Marvin Gaye.

After Gordy had established Motown and several subsidiary labels, he signed what he hoped would be a more lucrative deal, licensing his labels to EMI for U.K. distribution.

One of The Beatles’ first indirect brushes with Motown, interestingly, was through Geoff Emerick; as he detailed in his autobiography “Here, There, and Everywhere.” One of his earliest jobs was remastering American records sent to EMI for U.K. distribution. “My job was especially demanding when Tamla Motown material came in. I was always striving to match their full, bass-rich sound, but I found that I couldn’t ever do it successfully, which was quite frustrating,” Emerick wrote. “It took me a long while to realize that the reasons had to do with the equipment we had at EMI, which was not up to the standard of American equipment.”

Back on American soil, Gordy welcomed a special visitor to Hitsville in early 1964: Brian Epstein. As he described in “To Be Loved,” Epstein wanted to tell Gordy how much he and The Beatles loved the Motown Sound, “telling us of the great influence it had had on them.”

A few months later, Gordy received a call from a representative for Epstein. The Beatles wanted to record three Motown tracks for their second album: “Money,” “You Really Got a Hold on Me” and “Please Mr. Postman.” While Gordy was pleased to hear this, he was not thrilled with the offer: a discounted rate on the publishing royalty. Rather than pay Motown the standard 2 cents per song, Epstein’s office offered 1.5 cents. At first, Gordy turned down the offer flat, but the same man phoned the next day, stating Gordy had until noon to decide on the discounted publishing royalty rate. Gordy called Robinson, national sales and promotion manager Barney Ales and siblings Robert and Loucye Gordy into his office. After vigorous debate, Gordy reluctantly agreed to the discounted rate, deciding the potential sales were worth it.

“Everybody was jubilant that I had given in, including me — until about 2 o’clock that same day, when we got the news,” Gordy wrote. “Capitol Records had the albums in stock at their distributors and were, at that very moment, sending them out to radio stations and stores. The Beatles’ new album with our three songs on it, had already been recorded, mixed, mastered, pressed and shipped.”

Gordy may not have been pleased initially with the royalty rate, but the decision proved be a savvy one.

After failing to achieve more hits, Motown finally achieved a U.K. hit with Mary Wells’ “My Guy,” the single peaking at No. 5 in June, 1964. The Beatles declared themselves fans, calling Wells “their sweetheart,” and inviting her to open for them on their brief British tour from Oct. 9 to Nov. 10. A key element to Motown’s success in England proved to be The Beatles, whose Motown covers on “With The Beatles” further exposed British audiences to the label. To capitalize on the success, Gordy sent the label’s biggest stars — Wells, the Supremes, Martha Reeves and the Vandellas, the Miracles and the Temptations — on a promotional tour of the U.K. in October of that year. The Supremes’ November “Top of the Pops”appearance propelled “Baby Love” to No. 1, finally bringing Motown its first massive U.K. hit.

British audiences received Motown groups enthusiastically; in turn, the Supremes demonstrated their mutual admiration by releasing the album “A Bit of Liverpool” and posing for promotional photos imitating The Beatles’ “Please Please Me” album cover.

Still frustrated with Motown’s slow growth in the U.K., Gordy requested a meeting with a meeting with Tamla-Motown Appreciation Society founder and journalist Dave Godin in Detroit to discuss how to make better inroads with Britain. Godin suggested a specific brand to distinguish Motown; thus, Gordy launched the Tamla Motown label under the EMI umbrella in 1965. To coincide with the launch, as well as the release of the new label’s single, the Supremes’ “Stop! In the Name of Love,” the Motown Revue embarked on a 21-date leg of their package tour. A “Ready Steady Go!” special, entitled “The Sounds of Motown,” hosted by Dusty Springfield, featured the Supremes, Robinson and the Miracles, Stevie Wonder, the Temptations, Martha Reeves and the Vandellas and Gaye.

It was during the Motown Revue package tour that Gordy finally met The Beatles in person. As Gordy describes in “To Be Loved,” he took his father and kids to meet the group. “While taking photographs together, I told them how thrilled I was with the way they did our three songs in their second album. They told me what Motown music had meant to them and how much they loved Smokey’s writing, James Jamerson’s bass playing and the big drum sound of Benny Benjamin,” he said. Gordy appeared impressed by their knowledge of all the Motown artists, noting how John Lennon pronounced Marvin Gaye’s name as “Guy” In his Liverpudlian accent. While Gordy’s kids remained starstruck, Gordy’s father was less so. “Pop pulled two of the Beatles aside, telling one of his stories about how hard work pays off. I tried to rescue them by telling Pop we had to go, but they said they wanted to hear more,”

When Wells departed the label, Brenda Holloway initially was groomed to be the next “first lady” of Motown (soon to be displaced by the Supremes). Her first hit, 1964’s “Every Little Bit Hurts,” launched her career. By 1965, her hit-making prowess had faded a bit, but her single “Operator” performed well enough to earn her a spot opening for The Beatles on their 1965 U.S. tour (a recording of her performance is part of the Shea Stadium show).

At just 19, Holloway clearly appreciated the opportunity. In a Sept. 25, 1965, interview with KRLA Beat, Holloway enthusiastically proclaimed her love for the group. “[They are] real nice. They’re down to earth. They’re just people — that’s why I like them. They’re very friendly and I like them a whole lot!”

She shared some amusing anecdotes: “Ringo borrowed my hairdryer to do his hair. We had pillow fights. George usually started them and then everyone joined in. And Ringo would walk down the aisle of the plane saying: ‘Fasten your seat belts. Only doing my job!’”

Holloway added that “Ringo’s hair is the prettiest. He doesn’t have too much to say to anyone. Except one night he and the drummer from the King Curtis Band got into a long discussion on God and religion.”

After the tour ended, she said, “If they’d been crabs or mean I wouldn’t have enjoyed it. I miss them now that the tour is over.”

The tour would prove to be the highlight of her performing career; Holloway found more success as a backing vocalist and songwriter.

The Supremes Meet The Beatles

Despite The Beatles’ enormous popularity, Motown managed to hold its own in the 1960s. The Supremes, the label’s most successful act, proved to be The Beatles’ biggest competitor, in terms of No. 1 hits. In an Aug. 28, 2019, interview with Gold, Mary Wilson described a friendly rivalry. “I didn’t really think about it much then, but sometimes they would be No. 2, and we would be No. 1. Sometimes they were No. 1, we were No. 2,” she said. “So, we did have this thing going on. It was never really, as you said, a competition between us. Maybe our producers and all. I think they may have said, ‘Oh, boy, this female group is No. 1. We better get another hit record out there.’”

Wilson said the Supremes met The Beatles briefly during their first 1964 London visit, but their 1965 New York encounter proved much more memorable.

While in New York to tape an “Ed Sullivan Show” appearance, a meeting with The Beatles was arranged. “We wore smart, elegant day dresses, hats, gloves, high heels and jewelery, as well as fur jackets, Flo (Florence Ballard) in chinchilla, me in red fox and Diane (Diana Ross) in mink,” Wilson recalled. “We entered The Beatles’ suite, perfectly poised. Apparently, other people had been up to visit them earlier, including Bob Dylan and The Ronettes. The first thing I noticed was that the room reeked of marijuana smoke, but we kept on smiling through our introductions.”

Wilson felt unwelcome, that The Beatles were largely distant. “Paul was nice, but there was an awkward silence for most of the time. Every once in a while, Paul, George or Ringo would ask us about the Motown sound, or working with Holland-Dozier-Holland, then there would be silence again. … John Lennon just sat in the corner and stared.” The Supremes couldn’t wait to leave.

Years later, while Wilson visited Harrison in England, he told her, “We expected soulful, hip girls. We couldn’t believe that three black girls from Detroit could be so square!’”

Motown’s Influence on The Beatles

As previously noted, The Beatles most likely first heard Motown records as early as 1959, when Decca first issued early singles such as “Come to Me.” Ringo Starr stated in the “Anthology” documentary that “when I joined The Beatles, we didn’t really know each other, but if you looked at each of our record collections, the four of us had virtually the same records. We all had the Miracles, we all had Barrett Strong and people like that. I supposed that helped us gel as musicians, and as a group.”

As McCartney learned the bass, he listened to the melodic bass lines of Jamerson, even though he didn’t even know his name for many years. Jamerson’s jazz-influenced playing and distinctive bass lines in tracks such as the Temptations’ “My Girl” expanded the possibilities for bass players, teaching McCartney to avoid stagnant, clichéd lines (for examples of Jamerson’s inventiveness, listen to Gaye’s “What’s Going On” or the Four Tops’ “Standing in the Shadows of Love”).

As Mark Lewisohn notes in “Tune In: The Beatles All These Years,” when Ronnie Spector first met the group, she was shocked at how they “knew every Motown song ever put out.”

Robinson and the Miracles were a particular influence, as demonstrated on the “Please Please Me” track “Ask Me Why.” From Lennon’s falsetto to the backing vocals to the dramatic bridge (“I can’t believe it’s happened to me / I can’t conceive of any more misery”), Robinson and the Miracles’ style resonates throughout the track.

Indeed, as George Martin said in “Anthology,” “In the early days, they were very influenced by American rhythm-and-blues. I think that the so-called ‘Beatles sound’ had something to do with Liverpool being a port … They certainly knew much more about Motown, about black music, than anybody else did, and that was a tremendous influence on them.”

The Beatles would prove it with the B-side of the U.K. “I Want to Hold Your Hand” single, “This Boy,” a close-harmony track that Harrison described as ”a song John did that was very much influenced by Smokey. … If you listen to the middle eight of ‘This Boy,’ it was John trying to do Smokey,” he told Timothy White in “George Harrison Reconsidered.”

However, “With The Beatles” demonstrates not only their love of Motown, but their ability to cover and make the songs their own. “Please Mr. Postman” features a harder beat and Lennon’ raspy, harder-rock vocal, yet retains its R&B roots. “Money (That’s What I Want)” also receives a harder treatment, once again utilizing Lennon’s hard-charging style. Yet, the similar bluesy piano remains, as does the essential soul of the original. While “You Really Got a Hold on Me” has a slightly harder-rocking sound than the Robinson original, The Beatles’ largely remained faithful to the arrangement. As Ian Mac Donald wrote in “Revolution in the Head,” “Lennon offers a passionate lead vocal, which makes up in power what it wants for nuance beside the exquisite fragility of Smokey Robinson. If the final score is a draw, that is remarkable tribute to The Beatle’ versatility as interpreters.”

To demonstrate their mastery of the Motown sound, “All I’ve Got to Do,” with Lennon’s soulful lead vocal and Harrison and McCartney’s backing harmonies, has all the makings of a perfect girl-group, Marvelettes-like track.

“A Hard Day’s Night” finds them exploring more sounds, with the Motown influence lingering in the opening drumbeat and chords of “Tell Me Why.” In “The Beatles as Musicians: The Quarry Men through Rubber Soul,” musicologist Walter Everett notes that the “Help” track “You’re Going to Lose That Girl’ owes a lot to the Motown Sound, particularly in its “Motown-based responsorial backing vocals by Paul and George.” He cites Jacqueline Warwick’s analysis of backing-vocal girl groupisms, where she fantasizes Motown choreography for the song: “It’s easy to picture Paul and George shimmying and wagging their fingers if only they hadn’t instruments to contend with.”

Also, in a 1980 interview, Lennon described “When I Get Home” as “another Wilson Pickett, Motown sound … a four-in-the-bar cowbell song.”

While known primarily as a folk-influenced album, “Rubber Soul” does contain some elements of Motown. McCartney once described “You Won’t See Me” as “very Motown-flavored. It’s got a James Jameson feel,” according to Keith Badman’s “The Beatles: Off the Record.” Indeed, the “la la” backing vocals could come straight out of a Supremes record. And, “Drive My Car” contains the kind of clever lyrics that Robinson or Gordy might have written.

The Beatles also wanted to emulate the Funk Brothers’ sound, specifically the deep bass. Emerick recalled McCartney approaching him with a special request during the “Paperback Writer” sessions. “Paul turned to me. ‘Geoff,’ he began, ‘I need you to put your thinking cap on. This song is really calling out for the deep Motown bass sound we’ve been talking about, so I want you to pull out all the stops this time. All right, then?’”

Emerick described how often he and McCartney would meet in the mastering room to listen to “the low end of some new import he had gotten from the States, most often a Motown track.” He then brainstormed an idea: using a loudspeaker as a microphone. “I was able to achieve a good bass sound by placing it up against the grille of a bass amplifier, speaker to speaker, and then running the signal through a complicated setup of compressors and filters.”

While “Paperback Writer” may not seem to be derived from Motown, the bass sound was inspired by it.

One of the most obvious Motown tributes, “Got to Get You into My Life” on “Revolver,” represented The Beatles diving head-first into soul. In a 1968 interview with Jonathan Cott, Lennon described it as “our Tamla Motown bit. You see, we’re influenced by whatever’s going. Even if we’re not influenced, we’re all going that way at a certain time.” The horns, the lush production — all reflected Motown at its best.

“Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band” may have been firmly rooted in the psychedelic age, but as Steven Stark notes in “Meet the Beatles: A Cultural History of the Band That Shook Youth, Gender, and the World,” all the album’s songs follow one element of Gordy’s songwriting — all are in the present tense, a tactic that directly engages the listener. While that may not have been intentional, it might have resulted from years of listening to Motown lyrics.

In turn, Motown songwriters and producers were listening to The Beatles’ 1967 psychedelic sounds, and songs like the Supremes’ “Reflections” and the Temptations’ “Cloud Nine” soon followed.

During the recording of the White Album, while recording a take of “While My Guitar Gently Weeps,” the version broke down when Harrison tried to emulate Robinson’s falsetto vocals. “It’s OK,” he laughed. “I tried to do a Smokey, and I just aren’t Smokey.”

Motown was present elsewhere, however: McCartney’s melodic bass on the irregular time changes of “Happiness Is a Warm Gun” would make Jamerson proud.

Motown also clearly was on their minds during the “Get Back” sessions. Among the many song fragments The Beatles performed were such Motown hits as Gaye’s “Hitch Hike,” the Miracles’ “I’ve Been Good to You,” “You Really Got a Hold on Me,” and “The Tracks of My Tears,” the Shirelles’ “Love Is a Swingin’ Thing” and Strong’s “Money (That’s What I Want).”

Years later, McCartney revealed during a 2015 talk at the Liverpool Institute for the Performing Arts that Motown also taught him what to avoid in music. “I mean, you’d hear like the Supremes and Motown, Diana Ross’ group, those records are very similar,” McCartney said. “‘Stop! In the Name of Love’ or ‘Baby Love,’ they’re all very similar things. We wanted to avoid that. So, I think that was one of the good things for us, because we just kept on going and never sort of did the same song twice.”

While Motown did change its sound in the late 1960s and early 1970s — Whitfield served as an essential catalyst — the production-line model Gordy adapted from the Ford motor plant clearly did not suit The Beatles.

An Enduring Love Affair

Numerous Motown artists covered Beatles hits, although none had as much success as Wonder with his soulful rendition of “We Can Work It Out.” Appearing on his 1970 album “Signed, Sealed, Delivered,” it was released as a single in 1971. The single reached No. 13 on the Billboard Hot 100, earning him his fifth Grammy Award nomination in 1972, for Best Male R&B Vocal Performance. Almost 20 years later, Wonder would perform that version as McCartney was presented with a Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award in 1990. As he gave his acceptance speech, McCartney noted how “Fingertips” inspired The Beatles back in the early 1960s.

Wonder performed his cover again when McCartney was awarded the Gerswhin Prize by the Library of Congress in 2010, and once more at the Grammys Beatles tribute in 2014.

After The Beatles disbanded, the group still expressed their love of R&B. Harrison’s admiration for Robinson never dimmed, illustrated by “Ooh Baby (You Know That I Love You),” the “Extra Texture (Read All About It)”track intended as a companion piece to “Ooh Baby Baby.” His most compelling tribute, “Pure Smokey,” from “33 1/3,” outlines why Harrison held Robinson in high regard: “I wrote ‘Pure Smokey’ on ‘33 1/3’as my little tribute to his brilliant songwriting and his effortless butterfly of a voice,” he told White.

On “Cloud Nine,” Harrison gave Robinson one more shoutout on the track “When We Was Fab,” singing, “And you really got a hold on me.” Starr covered “Where Did Our Love Go?” for his 1978 “Bad Boy”album, and “Money (That’s What I Want)” for 2019’s “What’s My Name.”

Lennon may not have recorded Motown covers, but his personal jukebox included “First I Look at the Purse” by the Contours and several tracks by the Miracles: “The Tracks of My Tears,” “Shop Around,” “Who’s Lovin’ You,” “I’ve Been Good to You” and “What’s So Good about Goodbye.”

As for McCartney, not only did he cover Gaye’s “Hitch Hike” during his 2010 concert at New York’s Apollo Theatre, he visited the Motown Museum in Detroit in 2011 and volunteered to pay for refurbishing the studio’s 1877 Steinway grand piano. After work was completed in August, 2012, McCartney and Gordy played it together during a September charitable event at Steinway Hall in New York City. The piano now sits in Studio A at Hitsville USA in Detroit. McCartney also collaborated with two Motown artists: Wonder, on both “Ebony and Ivory” and “What’s That You’re Doing,” as well as a guest appearance on Wonder’s 2005 album “A Time to Love”; and Michael Jackson, on the “Thriller” duet “The Girl Is Mine” and the “Pipes of Peace” tracks “Say Say Say” and “The Man.”

Clearly, The Beatles and Motown owe a great deal to one another in terms of musical influence and exposure to wider audiences. In a “Motown 25: Yesterday, Today, Forever”DVD reissue, Robinson and original Temptations member Otis Williams discussed the relationship between Hitsville USA and the Fab Four. “They were the first huge white act to admit, ‘Hey we grew up with some black music. We love this,” Robinson said. Wilson added, “We knocked down those barriers, and I must give credit to The Beatles. It seemed like at that point in time white America said, ‘OK if the Beatles are checking them out, let us check them out.’”

As for The Beatles, Motown influenced them as songwriters, vocalists and instrumentalists, as a group and as solo artists — truly a two-way relationship.

Kit O’Toole