This is the complete, unedited version of Duncan Driver’s article excerpted in Beatlefan #243.

‘… don’t you know that you can count me out, in.’

— Sung by John Lennon on the song ‘Revolution I’ (1968).

One of the most astute observations made by historian and biographer Mark Lewisohn is that ‘the Beatles began to break up the day they got together.’ As with many divorces, differences that would become irreconcilable were present from the very beginning of their union: the decision to freeze George out of the Lennon-McCartney writing credit; Paul’s tendency towards bossiness and his refusal to be bossed around by anyone (except, perhaps, by John); most especially John’s rush to embrace and haste to discard new fads and sources of inspiration. Equally true of relationships that fall apart was the fact that happy and hopeful periods occurred until the very end: whether that end really was the end remained uncertain until later than you might think. As Ringo confirmed in The Beatles: Anthology, ‘There was always the possibility that we could have carried on.’ The reasons why the Beatles broke up are complex and fascinating, but it is beyond the scope of this article to explore them in great detail. Instead, it investigates how and when they broke up, recognising the process as iterative and the reasons as ubiquitous.

The first incarnation of the band that called itself ‘the Beatles’ could easily have disintegrated in late 1960, when an under-age George was deported from Hamburg and Paul and Pete (Best) were jailed for arson. Despite such dramatic events happening in a single day, nobody from the band bothered to contact each other for a fortnight, Mona Best (Pete’s mother) stirring them to action with a series of new-year phone calls. Lewisohn argues in Tune In that another break-up was imminent just a year later: by late 1961 the Beatles had achieved all that Liverpool offered and they could easily have stagnated had Brian Epstein not entered their story, elevating their presentation and exposure to a professional level. On the brink of unprecedented success in 1962, John speculated in a television interview about how long the group might last, considering a ten-year lifespan unrealistically ‘big-headed’. Fast-forwarding to Christmas 1966, a reporter who buttonholed each Beatle arriving at Abbey Road (then EMI Recording Studios) was clearly concerned by potential signs of disharmony and lethargy, asking ‘Are the Beatles going to go their own way in 1967?’, ‘What’s all this about the Beatles are going to do less together in the new year?’ and ‘Do you foresee a time when, in fact, the Beatles won’t be together and that you’ll all be on your own?’ John, George and Ringo each dismiss these entreaties, confident (at least for the camera) that they aren’t yet tired of each other and that the British public need not be concerned about the demise of the band. Behind closed doors, things may have been a little different. Earlier that year Paul had stormed out of the final recording session for Revolver, leaving George to play bass guitar on ‘She Said She Said’. There may not have been any serious intention to quit attached to this fit of pique, but it presaged Ringo leaving sessions for The Beatles (the White Album) in 1968 and George doing the same nine days into recordings for what would become Let it Be.

It is these January 1969 sessions that many focus on when investigating the break-up of the Beatles. Better documented than any of their other projects (and so subject to more intense speculation), 150 hours of nagra audiotape recorded every joke, comment and argument for posterity, the subject of ‘divorce’ being raised more than once. On January 7 (just six days into sessions), the band discussed the sour atmosphere at their Twickenham location, George reflecting that ‘the Beatles have been in the doldrums for at least a year’ before admitting, ‘we should have a divorce.’ Paul, usually the most enthusiastic Beatle, agreed: ‘Well, I said that at the last meeting. But it’s getting near it.’ John – uncharacteristically withdrawn until this point – joked, ‘Who’d have the children?’, but it is Paul who supplied the punchline: ‘Dick James’ (their music publisher). The discussion is surprisingly frank: nobody sounds angry or bitter. Hearing their dialogue, you’d be forgiven for thinking this wasn’t the first time they’d explored going their separate ways. Even more surprising is how they chose to spend the rest of the day: working collectively and enthusiastically on ‘I’ve Got a Feeling’, one of the true Lennon-McCartney collaborations of this period.

Three days later, George spoilt a lunch break by announcing that he was ‘leaving the group.’ John’s single-word question isn’t ‘What?’ or ‘Why?’, but ‘When?’, again suggesting that George had re-opened an ongoing conversation. ‘Now’ is George’s answer, delivered in a drawl before the parting quip, ‘See you ‘round the clubs.’ The effect on John is galvanising. Despite what he’d say later about the misery of the Let it Be sessions and his own desire to escape them, George’s departure turned on John’s bandleader switch: ‘I think if George doesn’t come back by Monday or Tuesday we ask Eric Clapton to play on it … the point is if George leaves, do we wanna carry on the Beatles? I say yes.’ It’s left for Paul to become unusually quiet at this point, noodling away on the piano in the background. An emergency band meeting was held two days later (without the nagra tapes running) at which George re-affirmed his decision to leave. The band met again on January 15, George agreeing to re-join on the condition that sessions move from Twickenham to the Beatles’ own studio in the basement of their Saville Row building.

Three days later, George spoilt a lunch break by announcing that he was ‘leaving the group.’ John’s single-word question isn’t ‘What?’ or ‘Why?’, but ‘When?’, again suggesting that George had re-opened an ongoing conversation. ‘Now’ is George’s answer, delivered in a drawl before the parting quip, ‘See you ‘round the clubs.’ The effect on John is galvanising. Despite what he’d say later about the misery of the Let it Be sessions and his own desire to escape them, George’s departure turned on John’s bandleader switch: ‘I think if George doesn’t come back by Monday or Tuesday we ask Eric Clapton to play on it … the point is if George leaves, do we wanna carry on the Beatles? I say yes.’ It’s left for Paul to become unusually quiet at this point, noodling away on the piano in the background. An emergency band meeting was held two days later (without the nagra tapes running) at which George re-affirmed his decision to leave. The band met again on January 15, George agreeing to re-join on the condition that sessions move from Twickenham to the Beatles’ own studio in the basement of their Saville Row building.

As with the marked swing from despondency to enthusiasm evident on January 7 when the band began rehearsing ‘I’ve Got a Feeling’, the move from Twickenham had an ameliorative effect on morale. Billy Preston’s arrival on January 22 also appears to have injected energy into proceedings, the arrangement for ‘Get Back’ (earmarked as the next single) coming together in just one day. Footage from these sessions included in the Let it Be film and in The Beatles: Anthology would appear to vindicate the claim that these late January sessions were a noticeably happy and remarkably productive couple of weeks, yielding not just the bulk of recordings issued as Let it Be but which also introduced the majority of songs from Abbey Road as well as some that would achieve fruition on future solo albums. So much for the claim that Let it Be documents a band breaking up: on the penultimate day of the month they can be seen enjoying every moment of live performance on the Apple office rooftop, decidedly passing their audition. Indeed, Paul was moved to send Ringo a postcard the next day on which was written (in block capitals), ‘YOU ARE THE GREATEST DRUMMER IN THE WORLD. REALLY.’

However close to ‘divorce’ they may have gotten in the early days of 1969, simple facts demonstrate that they did not break up at the time: less than a month after their rooftop performance they began recording ‘I Want You (She’s So Heavy)’, marking the beginning of the cohesive and focused Abbey Road sessions. A spanner was thrown into the works of what George Martin called ‘a very happy album’ on May 9, however, after a playback of material from the January sessions. An argument developed over the appointment of Allen Klein as the Managing Director of Apple Corps. Klein had wined and dined John (and Yoko) earlier that month, winning them over in the course of an evening; John had subsequently convinced George and Ringo to climb on board with Klein, but Paul had demurred signing the management contract. Paul remembers the argument in the Anthology this way:

The other three said, ‘You’ve got to sign a contract – he’s got to take it to his board.’ I said, ‘It’s Friday night. He doesn’t work on a Saturday, and anyway Allen Klein is a law unto himself. He hasn’t got a board he has to report to. Don’t worry – we could easily do this on Monday. Let’s do our session instead. You’re not going to push me into this.’

They said, ‘Oh, are you stalling? He wants 20%.’ I said, ‘Tell him he can have 15%.’ They said: ‘You’re stalling.’ I replied, ‘No, I’m working for us; we’re a big act.’ I remember the exact words: ‘We’re a big act – The Beatles. He’ll take 15%.’ But for some strange reason (I think they were so intoxicated with him) they said, ‘No, he’s got to have 20%, and he’s got to report to his board. You’ve got to sign now or never.’ So I said, ‘Right, that’s it. I’m not signing now.’

It’s hard not to see this from both perspectives. Paul raised real concerns about Klein’s motives and the Beatles’ bargaining power, while the accusation of ‘stalling’ appears legitimate: if Paul was happy to sign the contract on Monday, why not sign it on Friday? Reading between the lines of this, it would seem that the other three were forcing Paul’s hand, trying to get him to declare intentions he may have been cagey about. Speaking elsewhere of this three-against-one situation, Paul referred to it as ‘the crack in the liberty bell’, an excellent metaphor for The Beatles’ business differences that had begun to overshadow their music. Indeed, the metaphor is so strong that it’s worth extending to make a point about that music: the bell may have been cracked, but it had never produced a better sound.

There has been much discussion in recent years about the extent to which Abbey Road was the Beatles’ intentional swan-song, a final unified effort made possible because everyone involved knew it to be final. Allan Kozinn has written assiduously about this in issue #241 of Beatlefan, and so the arguments for and against the claim will not be resuscitated here. It is true that the album works well as a final artistic statement, ‘The End’ closing the Beatles’ career with the neatly Shakespearean couplet, ‘And in the end, the love you take / Is equal to the love you make’. What tends to be forgotten when this is pointed out, however, is that ‘The End’ is not how Abbey Road ends: after 17 seconds of silence, the final note of ‘Mean Mr Mustard’ is heard, before Paul sings his little ditty about ‘Her Majesty’. Famously, the final ‘D’ of this short piece of whimsey is cut, effectively ending the album on an unresolved note. The original track sequence for the album, moreover, identified Side B as Side A and vice versa: Abbey Road was going to end with ‘I Want You (She’s So Heavy)’, also a song that ends abruptly. For all the talk of Abbey Road tying a neat ribbon around the Beatles’ body of work, then, it must be acknowledged that the album’s aesthetic insists on that work as unfinished, perhaps even suggesting that the Beatles’ career is far from certain – neither continuing as before, nor completely over. As Ringo’s confirmed in the Anthology, the door was self-consciously open to ‘possibility’.

There has been much discussion in recent years about the extent to which Abbey Road was the Beatles’ intentional swan-song, a final unified effort made possible because everyone involved knew it to be final. Allan Kozinn has written assiduously about this in issue #241 of Beatlefan, and so the arguments for and against the claim will not be resuscitated here. It is true that the album works well as a final artistic statement, ‘The End’ closing the Beatles’ career with the neatly Shakespearean couplet, ‘And in the end, the love you take / Is equal to the love you make’. What tends to be forgotten when this is pointed out, however, is that ‘The End’ is not how Abbey Road ends: after 17 seconds of silence, the final note of ‘Mean Mr Mustard’ is heard, before Paul sings his little ditty about ‘Her Majesty’. Famously, the final ‘D’ of this short piece of whimsey is cut, effectively ending the album on an unresolved note. The original track sequence for the album, moreover, identified Side B as Side A and vice versa: Abbey Road was going to end with ‘I Want You (She’s So Heavy)’, also a song that ends abruptly. For all the talk of Abbey Road tying a neat ribbon around the Beatles’ body of work, then, it must be acknowledged that the album’s aesthetic insists on that work as unfinished, perhaps even suggesting that the Beatles’ career is far from certain – neither continuing as before, nor completely over. As Ringo’s confirmed in the Anthology, the door was self-consciously open to ‘possibility’.

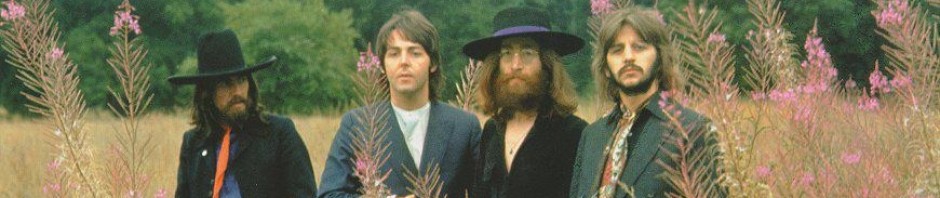

After completing Abbey Road and conducting what would be their final photo session on August 22, another suggestion of a 3-1 split in The Beatles (with Paul in the minority) may be the fact that John, George and Ringo attended the Isle of Wight concert together on August 30-31 and Paul did not. The grain of salt to take this with, however, is that Paul’s first child (Mary) had been born just two days earlier. Reading his absence as a sign of disharmony is speculative, especially as the band (minus Ringo, waylaid in hospital with an intestinal complaint) would meet on September 8 to discuss arrangements for their next album and a potential Christmas single. Given Ringo’s absence, the meeting was taped (and subsequently reproduced in Anthony Fawcett’s One Day at a Time: John Lennon). John chairs the meeting and proposes that he, Paul and George each bring their four best songs to the as-yet-unscheduled recording sessions. This, John admits, is an attempt at equality recognising George’s recent flowering as a songwriter and driven by guilt at how he and Paul had ‘carved up’ the Beatles’ extant empire between themselves. A meekly quiet Paul considers such strict rationing of album space to be ‘like the army’ before John and George begin a loaded exchange about effort expended on Harrison compositions in contrast to Lennon-McCartney offerings. John’s voice appears defensive and hurt as it claims that George tended to prefer the contributions of ‘Eric or somebody like that’ to those of his bandmates. There is a pregnant silence before Paul, almost inaudibly, whispers ‘When we get into a studio, even on the worst day, I’m still playing bass, Ringo’s still drumming, and we’re still there, you know.’

On September 12, the promotor John Brower phoned the Apple office to offer John and Yoko tickets to the Toronto Rock and Roll Revival festival scheduled for the following day. To his surprise, John accepted on the condition that he could perform at the event, a condition that Brower did not hesitate agreeing to. George recalls this in the Anthology:

When the Plastic Ono Band went to Toronto in September John actually asked me to be in the band, but I didn’t do it. I didn’t really want to be in an avant-garde band, and I knew that was what it was going to be.

He said he’d get Klaus Voormann, and Alan White as the drummer. During the last few years of The Beatles we were all producing other records anyway, so we had a nucleus of friends in the studios: drummers and bass players and other musicians. So it was relatively simple to knock together a band. He asked me if I’d play guitar, and then he got Eric Clapton to go – they just rehearsed on the plane over there.

Again, Paul may not have been asked on the understanding that his family were still adjusting to the arrival of a baby, and it is likely that Ringo was convalescing. George’s refusal is more revealing of rumbling within the Beatles’ ranks, especially his stated objection to John’s choice of extra-curricular projects (and their ‘avant-garde’ collaborators). When speaking to Jann Wenner for Rolling Stone in 1970, John remembers this as the day at which he decided to leave the Beatles:

We were in Apple and I knew before I went to Toronto, I told Allen [Klein] I was leaving. I told Eric Clapton and Klaus that I was leaving and I’d like to probably use them as a group. I hadn’t decided how to do it, to have a permanent new group or what. And then later on I thought, ‘Fuck it, I’m not going to get stuck with another set of people, whoever they are.’ So I announced it to myself and to the people around me on the way to Toronto the few days before. On the plane Allen came with me, and I told him, ‘It’s over.’

We were in Apple and I knew before I went to Toronto, I told Allen [Klein] I was leaving. I told Eric Clapton and Klaus that I was leaving and I’d like to probably use them as a group. I hadn’t decided how to do it, to have a permanent new group or what. And then later on I thought, ‘Fuck it, I’m not going to get stuck with another set of people, whoever they are.’ So I announced it to myself and to the people around me on the way to Toronto the few days before. On the plane Allen came with me, and I told him, ‘It’s over.’

The next day, John regretted having agreed to perform at the festival, but was convinced by Eric Clapton that it was too late to back out. During the flight back to London, on 15 September, John confided to journalist Ray Connelly that he had decided to leave the Beatles, asking him not to print this news just yet.

It was on September 20 that John made the sudden decision to inform Paul and Ringo of his intention. The band (minus George, who was visiting his mother) were present at the Apple office to sign a new contract with EMI/Capitol guaranteeing an increased royalty of 25% (up from 17.5%). A series of black-and-white photos from this event depict John (Yoko at his side), Paul and Ringo gathered around Allen Klein’s desk. One shot features John pretending to sign the document on Klein’s back as Paul feigns kissing his hand as though paying his respects to a Mafia Don. A band meeting followed at which Paul made a series of proposals for the future. He remembers this in the Anthology:

I’d said: ‘I think we should go back to little gigs – I really think we’re a great little band. We should find our basic roots, and then who knows what will happen? We may want to fold after that, or we may really think we’ve still got it.’ John looked at me in the eye and said: ‘Well, I think you’re daft. I wasn’t going to tell you till we signed the Capitol deal’ – Klein was trying to get us to sign a new deal with the record company – ‘but I’m leaving the group!’ We paled visibly and our jaws slackened a bit.

I didn’t really know what to say. We had to react to him doing it; he had control of the situation. I remember him saying, ‘It’s weird this, telling you I’m leaving the group, but in a way it’s very exciting.’ It was like when he told Cynthia he was getting a divorce. He was quite buoyed up by it, so we couldn’t really do anything: ‘You mean leaving’? So that’s the group, then…’ It was later, as the fact set in, that it got really upsetting.

Again, the prospect of breaking up is likened to a divorce. It is interesting that John’s admission seems to have left him ‘buoyed’, another case of excitement at leaping into the unknown with both feet. It is partly because John’s announcement appears to have been unplanned and instinctual (‘I wasn’t going to tell you’) that the other Beatles may have held out hope of a return to the fold. The decision itself had been made just seven days earlier, and John certainly had a history of turning cold on what he had recently been hot for. Consider his request to play at the Toronto Rock and Roll Revival festival and then his attempt to renege on the deal just one day later, his commitment to transcendental meditation in India and sudden departure amid accusations of inappropriate behaviour on the Maharishi Mahesh Yogi’s part, or his vocal enthusiasm for but failure to complete Arthur Janov’s Primal Scream therapy. It was certainly conceivable that John would change his mind about leaving The Beatles, and the lack of any public announcement about his decision could be put down to a ‘wait and see’ attitude on behalf of the other three or a recognition by John himself that public silence allowed him to keep his options open. We must remember that this was the man who, a year earlier, had sung ‘you can count me out, in’, admitting to a mercurial nature.

* * *

However much he may have been holding out hope for a change of heart, there is no denying that John’s request for a ‘divorce’ ‘got really upsetting’ for Paul, who decamped to his remote Scottish farm with his family and was so little seen or heard in the ensuing months that rumours of his death began to spread. John busied himself with ‘avant garde’ projects for the rest of the year, George toured as part of the Delaney & Bonnie band and Ringo set to work on Sentimental Journey, a solo album of old standards. On January 3 of 1970, Paul, George and Ringo convened at Abbey Road to arrange and record George’s song, ‘I Me Mine’ for inclusion on Let it Be. George can be heard alluding to John’s absence on take 16 as he jokes ‘You all will have read that Dave Dee’s no longer with us, but Micky and Titch and I would just like to carry on the good work that’s always gone down at Number 2 [recording studio].’ John’s absence could be put down to the fact that he was in Denmark at the time, trying to win a custody battle over Yoko’s daughter, Kyoko. It is quite possible, however, that if he were in London and available he would still have been reticent to participate in the session. His decision to leave the band may have held firm, or if it were wavering he might still have thought twice about showing up for one of George’s songs, a tendency alluded to in the September 8 meeting in 1969. The ‘threetles’ (minus John) finalised the song ‘Let it Be’ the next day with new vocal, guitar and bass parts.

However much he may have been holding out hope for a change of heart, there is no denying that John’s request for a ‘divorce’ ‘got really upsetting’ for Paul, who decamped to his remote Scottish farm with his family and was so little seen or heard in the ensuing months that rumours of his death began to spread. John busied himself with ‘avant garde’ projects for the rest of the year, George toured as part of the Delaney & Bonnie band and Ringo set to work on Sentimental Journey, a solo album of old standards. On January 3 of 1970, Paul, George and Ringo convened at Abbey Road to arrange and record George’s song, ‘I Me Mine’ for inclusion on Let it Be. George can be heard alluding to John’s absence on take 16 as he jokes ‘You all will have read that Dave Dee’s no longer with us, but Micky and Titch and I would just like to carry on the good work that’s always gone down at Number 2 [recording studio].’ John’s absence could be put down to the fact that he was in Denmark at the time, trying to win a custody battle over Yoko’s daughter, Kyoko. It is quite possible, however, that if he were in London and available he would still have been reticent to participate in the session. His decision to leave the band may have held firm, or if it were wavering he might still have thought twice about showing up for one of George’s songs, a tendency alluded to in the September 8 meeting in 1969. The ‘threetles’ (minus John) finalised the song ‘Let it Be’ the next day with new vocal, guitar and bass parts.

On January 5, whilst still in Denmark, John and Yoko gave a press conference at which John stated that ‘we’re not breaking up the band, but we’re breaking its image’, adding that the group would gather together and record an album before too long, if only for the money. John may have been putting a positive spin on what was still a serious intention to leave, but his comment about ‘breaking the image’ rather than the band cannot be dismissed as an outright lie. For one thing, it matches comments he had made in the January 1969 recording sessions about wanting the increasingly claustrophobic foursome of The Beatles to become a looser collective of ‘Beatles and Co.’ associate artists like Billy Preston. Paul had said much the same thing to Life in November of that year: ‘We make good music and we want to go on making good music. But the Beatle thing is over. It has been exploded…’ In concert with John’s comment about the break-up of the ‘image’ rather than the band, Paul seems to be suggesting that the myth of mop-topped fab four unity no longer existed, but that the possibility of music reflecting the band’s ‘real’ selves as distinct contributors to a shared identity remained possible. John would re-iterate this position to the BCC on February 6, stating that he ‘wouldn’t destroy [The Beatles] out of hand’ and that their current hiatus could prove either ‘a rebirth or a death’.

A little earlier that year (January 15), John and Yoko sent a curious postcard to Paul and Linda (McCartney) that read, ‘WE LOVE YOU AND WILL SEE YOU SOON.’ It is hard to know what to make of this: is it evidence that the bond between the two Beatles was still strong, or does it offer re-assurances of cordial relations at a time of strain? As it happens, Paul was not waiting aimlessly for John’s return. Having borrowed a four-track tape machine from EMI, he had been making experimental home recordings, likely unsure of whether the music might develop into a Beatles or solo project (or nothing at all). It is revealing that ‘Maybe I’m Amazed’ and ‘Every Night’ – the two most substantial songs to be released on McCartney – were not recorded at home on this rudimentary equipment, but professionally at Abbey Road on February 22 and 23. The dates are auspicious because it was not until February 6 that John released ‘Instant Karma!’, his first solo single to reach the top 5 of the UK and USA charts. Paul’s decision to make use of his old band’s preferred studio and to focus on these stellar compositions (the first of which had been brought to The Beatles in 1969) was likely a response to the quality of John’s new material. John would later describe the creative rivalry between his old writing partner and he as two men ‘scar[ing each other] … into doing something good’, and this is a prime instance.

George, who might be considered conspicuously quiet over the early months of 1970, had encouraging words to say about the future of the group on March 11, when interviewed by the BBC:

George, who might be considered conspicuously quiet over the early months of 1970, had encouraging words to say about the future of the group on March 11, when interviewed by the BBC:

I certainly don’t want to see the end of The Beatles. And I know I’ll do anything, you know. Whatever Paul, John, Ringo would like to do, I’ll do it. As long as we can all be free to be individuals at the same time.

I think that’s just part of our life, you know, is to be Beatles. And I’ll play that game, you know, as long as the people want us to.

This hopeful attitude appears to have been vindicated by at least one event 6 days later: on March 17, George held a birthday party for his wife (Pattie) at their new home in Henley-on-Thames. Apple staffer Chris O’Dell later recalled this as ‘a great success. Ringo and Maureen, Paul and Linda, John and Yoko … were all there.’ O’Dell’s statement was not a hasty press release aimed at papering over increasingly-visible cracks with lies or half-truths, but a personal reflection made after the event, and so it would seem to represent an accurate impression of good relations between the four Beatles, all present in one location in March 1970. When interviewed by the BBC on March 25, Ringo confirmed that the band were still very much together, blaming the British press for stirring unwarranted controversy around them. This doesn’t square with comments he made four days later, however, when appearing on Frost on Sunday. The titular host asked whether The Beatles were likely to record together again, Ringo admitting that this was doubtful. Had submerged arguments resurfaced in the intervening days? It is one of the minor mysteries of this uncertain time. Perhaps the discrepancy between Ringo’s statements is yet another case of uncertainty itself: things between the Beatles being fine but not fine, hopeful then doubtful, cohesive yet disintegrating, in very quick succession. If so, it supports this article’s claim that the lived experience of the period for John, Paul, George and Ringo was indeed one of doubt more than certainty; claims they would make later about the band having already broken up being susceptible to the selection of evidence that supports this view and forgetful of evidence suggesting otherwise.

Indeed, Ringo would again claim to the BBC that the Beatles would likely work together again on the morning of March 31, 1970. It was also on this day that a problem with potential release dates was identified at Apple, McCartney scheduled for April 10 and Let it Be for April 24. Without Paul being present, a decision was made to push the release of McCartney back to June 4, prioritising the group effort over a solo album. John was careful in communicating this decision to Paul, handwriting a note on which appeared these words:

Dear Paul, We thought a lot about yours and the Beatles LPs – and decided it’s stupid for Apple to put out two big albums within 7 days of each other (also there’s Ringo’s and Hey Jude) – so we sent a letter to EMI telling them to hold your release date til June 4th (there’s a big Apple-Capitol convention in Hawaii then). We thought you’d come round when you realized that the Beatles album was coming out on April 24th. We’re sorry it turned out like this – it’s nothing personal. Love John & George. Hare Krishna. A Mantra a Day Keeps MAYA! Away [sic].

The note was placed in an envelope, on which was written ‘From us to you’ and it was hand-delivered by Ringo to Paul’s house in St John’s Wood. Ringo would later remember what occurred next in an affidavit submitted in court in 1971:

I went to see Paul. To my dismay, he went completely out of control, shouting at me, prodding his fingers towards my face, saying: ‘I’ll finish you now’ and ‘You’ll pay.’ He told me to put my coat on and get out. I did so.

Paul’s account of their exchange in the Anthology is consistent with this, and both versions suggest that its intensity was out of character (‘it was the only time I ever told anyone to GET OUT!’). Clearly, the 3-to-1 situation had left Paul feeling increasingly isolated and overlooked, his lashing out at a bandmate almost a ‘fight or flight’ response to decisions made about his solo work by the three Beatles who had had nothing to do with its creation. It is not hard to feel sympathetic towards Paul here, but we must also recognise that if the hiring of Allen Klein was ‘the crack in the liberty bell’, and if John’s request for a divorce on September 20, 1969 seriously impacted the Lennon-McCartney relationship, then this was a third event that risked damaging The Beatles irreparably.

On April 9, Paul (surely mulling over recent events in the relative isolation of his family home) phoned John at Dr Arthur Janov’s private London hospital, where he was undergoing Primal Scream therapy. John would remember the conversation this way:

Paul said to me, ‘I’m now doing what you and Yoko were doing last year. I understand what you were doing’, all that shit. So I said to him, ‘Good luck to yer.’

Paul having won the previous month’s battle around release dates for albums, Apple staffers spent much of the same day packing review copies of McCartney with unusual ‘question-and-answer’ sheets intended to be a replacement for the normal round of interviews that attended an album’s release (Paul would later say that he was not capable of facing the press at the time). Derek Taylor had sent the questions to Paul at home, and Paul had supplied written responses to them (though Taylor would later confirm that those questions specific to the Beatles had been added by Paul himself). As the albums arrived on Fleet Street news desks and their inserts were read, rumours that Paul had left the Beatles began to swell. Mavis Smith, assistant to Derek Taylor, released a statement assuring the press that this was ‘just not true’. The Daily Mirror, however, confidently ignored this, preparing the headline ‘PAUL QUITS THE BEATLES’ for the next day.

Paul having won the previous month’s battle around release dates for albums, Apple staffers spent much of the same day packing review copies of McCartney with unusual ‘question-and-answer’ sheets intended to be a replacement for the normal round of interviews that attended an album’s release (Paul would later say that he was not capable of facing the press at the time). Derek Taylor had sent the questions to Paul at home, and Paul had supplied written responses to them (though Taylor would later confirm that those questions specific to the Beatles had been added by Paul himself). As the albums arrived on Fleet Street news desks and their inserts were read, rumours that Paul had left the Beatles began to swell. Mavis Smith, assistant to Derek Taylor, released a statement assuring the press that this was ‘just not true’. The Daily Mirror, however, confidently ignored this, preparing the headline ‘PAUL QUITS THE BEATLES’ for the next day.

When considering Paul’s responses in the questionnaire and their relationship to this headline, it is important to recognise that the words ‘I quit’ do not appear anywhere but in the Mirror’s sensationalist reportage. There has been a tendency in discussion of this questionnaire to conflate Paul’s words with the way they were received, interpreting a few of his statements as an unequivocal announcement that The Beatles had indeed reached the point of ‘divorce’. An objective consideration of Paul’s answers in the questionnaire, however, reveals that equivocating is exactly what he is doing: neither confirming nor denying a split, acknowledging that he is unhappy with the state of the band but recognising that relationships between its four members were far from over. The most relevant aspects of the questionnaire to this article are as follows:

Q: Will Paul and Linda become a John and Yoko?

A: No, they will become Paul and Linda.

Q: Did you miss the other Beatles and George Martin? Was there a moment when you thought, ‘I wish Ringo were here for this break?’

A: No.

Q: Are you planning a new album or single with the Beatles?

A: No.

Q: Is this album a rest away from the Beatles or the start of a solo career?

A: Time will tell. Being a solo album means it’s “the start of a solo career…” and not being done with the Beatles means it’s just a rest. So it’s both.

Q: Is your break with the Beatles temporary or permanent, due to personal differences or musical ones?

A: Personal differences, business differences, musical differences, but most of all because I have a better time with my family. Temporary or permanent? I don’t really know.

Q: Do you foresee a time when Lennon-McCartney becomes an active songwriting partnership again?

A: No.

It is understandable that Paul did not wish to see his marriage in terms of John and Yoko’s relationship, preferring instead to ‘ram on’ towards a unique identity. Not missing the other Beatles or their producer could easily be put down to the fact that the album under discussion was very different to the band’s work, much more of a family affair. At the risk of comparing Paul and Linda to John and Yoko, it was in some respects an answer to their 1969 Wedding Album: however much Paul might love his bandmates, he could be forgiven for preferring the company of his family during the honeymoon period of his marriage and the birth of his first child. Not planning a new album or single with the Beatles could be read as evidence that the band were defunct, but it should be remembered that long-term planning was never the Beatles’ modus operandi, even at their most cohesive. Indeed, the two projects that had suffered the most in the Beatles canon (Magical Mystery Tour and Let it Be) were problematic largely because of this preference for spontaneity over planning. Paul states in his next two answers that he is ‘not … done with the Beatles’ and that he doesn’t know whether the ‘break’ with the group is ‘temporary or permanent’. These are both far from being a declaration of independence. He may not have been able to foresee a time when Lennon-McCartney would again become an active partnership, but John and Paul’s song writing had been growing more distinctly individual for some time. Even on ‘happy’ albums like Abbey Road, certain songs belonged solely to Paul and others to John, despite the co-credit.

Paul’s private phone call to John might suggest an intention to leave as firm as John’s had been, but what he chose to announce publicly was considerably more tempered. He may have been trying to let the band’s fans down easy, but the fact is that his questionnaire remains another example of a Beatle declaring himself out-but-in. As Derek Taylor himself would state in a press conference on April 10, ‘He says himself he doesn’t know whether the break is temporary or permanent: that’s the truth.’ If Paul’s ‘self-interview’ marked a point beyond which The Beatles could not continue, it had less to do with the intent of the piece and more to do with its unfortunate effect. John’s response (‘Paul didn’t quit, I sacked him’) appears to reference the Mirror headline more than any of Paul’s statements, and perhaps Paul’s phone call to John the day before led him to assume a more direct connection between the ‘self-interview’ and its surrounding publicity than there actually was.

Paul’s private phone call to John might suggest an intention to leave as firm as John’s had been, but what he chose to announce publicly was considerably more tempered. He may have been trying to let the band’s fans down easy, but the fact is that his questionnaire remains another example of a Beatle declaring himself out-but-in. As Derek Taylor himself would state in a press conference on April 10, ‘He says himself he doesn’t know whether the break is temporary or permanent: that’s the truth.’ If Paul’s ‘self-interview’ marked a point beyond which The Beatles could not continue, it had less to do with the intent of the piece and more to do with its unfortunate effect. John’s response (‘Paul didn’t quit, I sacked him’) appears to reference the Mirror headline more than any of Paul’s statements, and perhaps Paul’s phone call to John the day before led him to assume a more direct connection between the ‘self-interview’ and its surrounding publicity than there actually was.

It would appear as if a regrettably unanticipated but intense period of jealousy, resentment, defiance and anger followed the events of April 9 and 10, further delineating Paul from the other three Beatles, who continued to work happily with each other over their various solo projects in 1970. Paul may have had little or no contact with them for some time after his phone call to John on April 9, but the final nail in the band’s coffin would not be hammered until the very last day of the year, on which Paul filed a lawsuit to dissolve the Beatles’ partnership. George had floated the idea of ‘divorce’ nearly two years earlier; John had requested this of his bandmates eight months later. Not all divorces are acrimonious, but those involving as much money and contractual obligation as The Beatles’ seldom end without the need of lawyers. A courtroom battle was, in one respect, the natural end-point of the ‘trial separation’ that had played itself out over 1970. It was almost as if Paul was responding directly to George’s original proposal and John’s direct request. It’s easy to imagine him thinking, as he signed the legal papers, ‘You want a divorce? You got it. This is how it happens.’

Dr Duncan Driver is an Assistant Professor at the University of Canberra in Australia. His PhD research investigated aspects of Shakespeare studies and movements in literary criticism, leading to articles for Melbourne Scholarly Publishing and Iona College’s Shakespeare Newsletter. More recently, Duncan has published “Writer, Reader, Student, Teacher” in English in Australia, “Poetry and Perspective” in Idiom, “Reflecting Windows: The Blade Runner Films in the English Classroom” in Screen Education and ‘Wordsworth’s ‘We Are Seven’” in Changing English. He is currently co-authoring a book on English teaching in secondary schools to be published by Cambridge University Press in 2020.

Pingback: 205: Countdown to Break-Up - Something About The Beatles

Pingback: 212: Countdown To Break-Up II - Something About The Beatles